Literature Notes: On-Device LLM Training

Published:

Collection of notes from papers on the topic of training LLMs (and where possible, ML models in general) on edge devices. Most software libraries and literature aimed at on device operation are aimed at efficient inference. Training on device is a less-developed area. Training on device is useful in applications where a model must be fine tuned for individual use cases.

Efficient Fine-Tuning of BERT Models on the Edge (2022)

Abstract

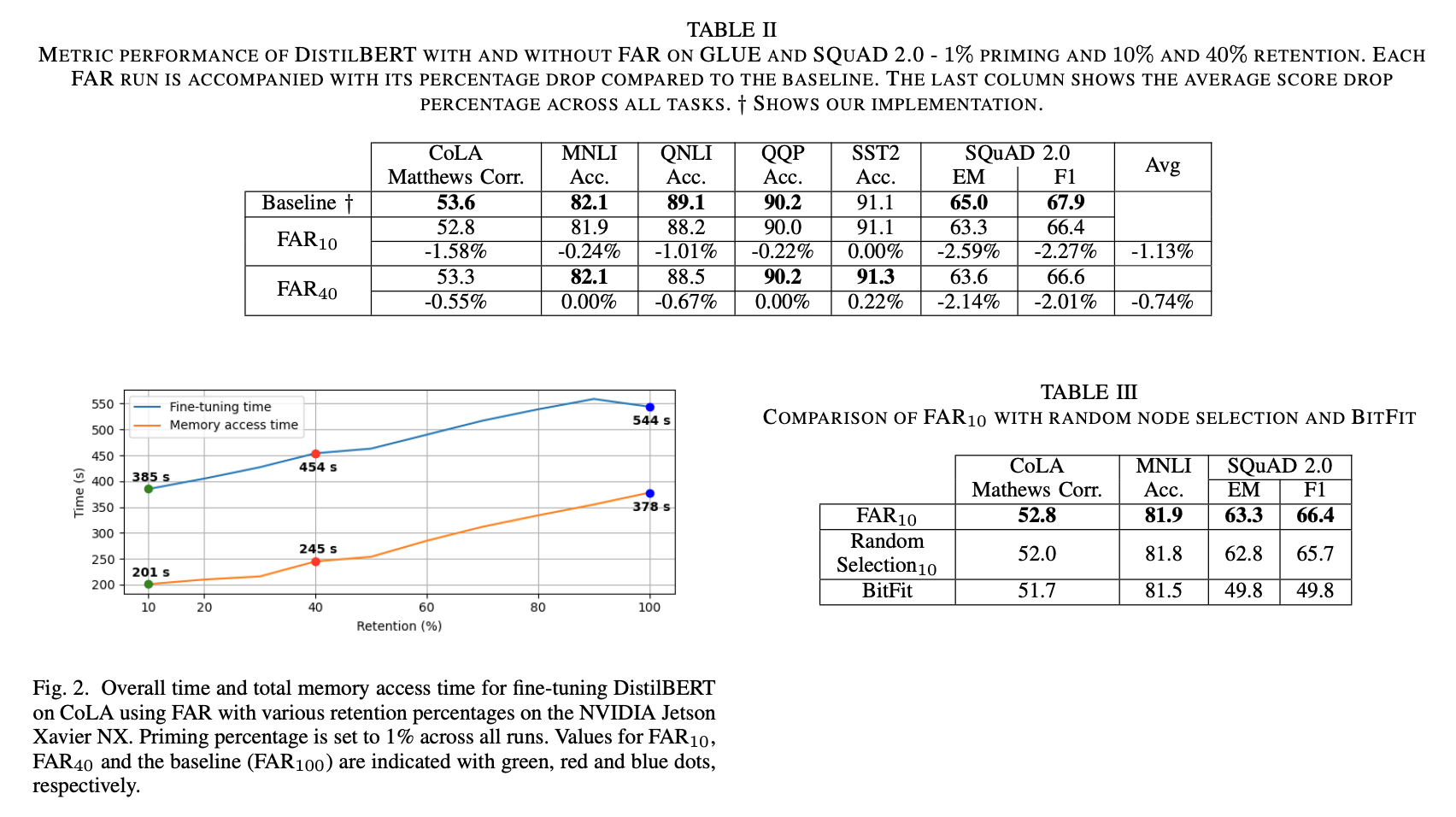

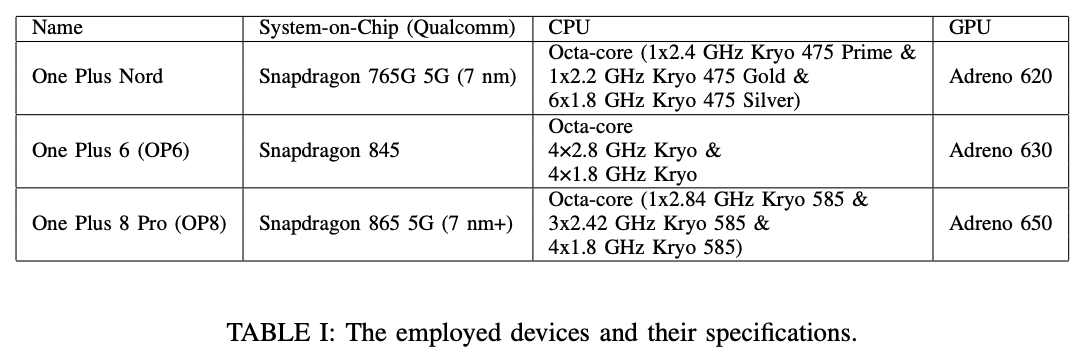

- Proposes Freeze and Reconfigure (FAR) approach. Increases training efficiency by reducing memory accesses in training of BERT-like models. FAR reduces training time on DistilBERT model and CoLA dataset by 30%. Reductions in metric performance on GLUE and SQuAD datasets are around 1% on average.

Introduction

- Training requires 3X more memory operations than inference. Especially bad since memory accesses to main memory are two orders of magnitude more energy intensive than computation. Model compression does not bridge the gap: a compressed model with 1/3 the size of the original is hard to achieve.

- During inference, only parameters and data are retrieved from memory (2 operations). During training, parameters must be retrieved at least twice and stored once, activations are stored and retrieved, data is retrieved (6 operations).

- Two techniques to achieve on-device learning are (a) using a compressed model to reduce baseline memory requirements and (b) training in a resource-efficient manner. FAR is intended to accomplish the latter.

- FAR has two elements: (a) a novel learning metric that tracks the size of weight updates over contiguous groups of parameters in order to indicate which groups should be frozen and (b) a novel parameter freezing scheme that regroups frozen and non-frozen parameters to reduce training time.

- Claimed results: if 60% of model parameters are frozen, fine-tuning time is reduced by 30%. Metric performance is maintained.

Background and Related Work

- Basic building block of BERT-like models is Attention and Feed Forward Network (FFN). FAR reconfigures these blocks. This paper’s proposed algorithm is intended to be used with compressed models like DistilBERT.

- Other approaches to efficient learning train only the best-learning weights while leaving others at their initialization values. This unstructured selection of weights leads to inefficient memory accesses.

Freeze and Reconfigure (FAR)

- In FAR, each FFN layer is considered a single group of parameters. These nodes are classified as learner and non-learner depending on how a node performs during fine tuning. The non-learner nodes are frozen. Reconfiguration of the FFN layers is completed during fine tuning by separating learner and non-learner nodes into distinct, newly created FFN sublayers.

- The set of learner nodes is decided upon after an initial set of fine-tuning iterations called priming. During priming, a copy of the pre-trained weights is made and some small % of the fine tuning iterations are performed. The initial FFN weight vectors are subtracted from the fine-tuned FFN weight vectors. The L1 norm is used to compute the total amount learned by each node in the FFN. Usage of the L1 norm allows for weights of the FFN node to be grouped so that architectural modifications can be made later for greater memory savings.

- To compute the set of learner nodes, a retention percentage is defined as the ratio of learner nodes to the total number of nodes. A more compressed model may require higher retention to avoid substantial losses in metric performance.

- FFNs in each transformer block are reconfigured to separate learner nodes from non-learner nodes. Such separation ensures that the memory of learner nodes is grouped together for optimal memory access patterns. To restore the output order of FFNs, a permutation is applied to output vectors. The combination of reconfiguration and permutation trades memory accesses for additional time spent on computation and data movement which are far less costly.

- Reconfiguration is also beneficial for practical implementation since in PyTorch, automatic gradient computation can not be disabled for single parameters but instead only whole layers or sublayers. No special hardware or libraries are required to implement FAR.

Alex’s Comments

The authors compare metric performance of FAR versus random selection in Table 3. In that table, it is clear that there is not a large metric performance improvement between FAR and random selection. However, the authors do not compare fine tuning time improvement of FAR vs random selection. They claim that the memory access pattern of random selection would make it much slower (which is a believable claim) but no data is provided to substantiate this.

Enabling On-Device Smartphone GPU based Training: Lessons Learned

Abstract

- The paper conducts an analysis to examine the feasibility of on-device training on smartphones using mobile GPUs.

- Observed that training on mobile CPUs is much faster than on mobile GPUs and identified two possible bottlenecks related to this observation: (i) computation and (ii) memory bottlenecks. To solve the computation bottleneck, the authors optimize the OpenCL backend’s kernels, showing 2x improvements (40-70 GFLOPs) over CPUs (15-30 GFLOPs) on the Snapdragon 8 series processors.

- However, full DNN training is still much slower on GPUs than on CPUs. This indicates that memory bottleneck plays a significant role in the lower performance of GPU over CPU. The data movement takes almost 91% of training time due to the low bandwidth.

Introduction

- Tasks done in the paper: (a) Investigate the feasibility of on-device training on smartphones using mobile GPUs. Evaluate to what extent operations can be optimized on a mobile GPU. (b) Optimize the MNN framework since it is open source and can run on Android and iOS devices and has an OpenCL backend. (c) Introduce kernel optimizations for the matrix multiplication kernels in OpenCL. These optimizations show speedups on One Plus 6 and One Plus 8 Pro. One Plus 6 and One Plus 8 Pro.

- Authors failed to gain improvements in the performance of full DNN training on the GPU.

- Memory bottlenecks hamper the overall goal of faster training for DNN using GPU (over CPU) on mobile devices. Profiling experiments demonstrate that it takes about 10-15X longer to copy data to and from the GPU than the actual computation time on all three devices.

Methodology

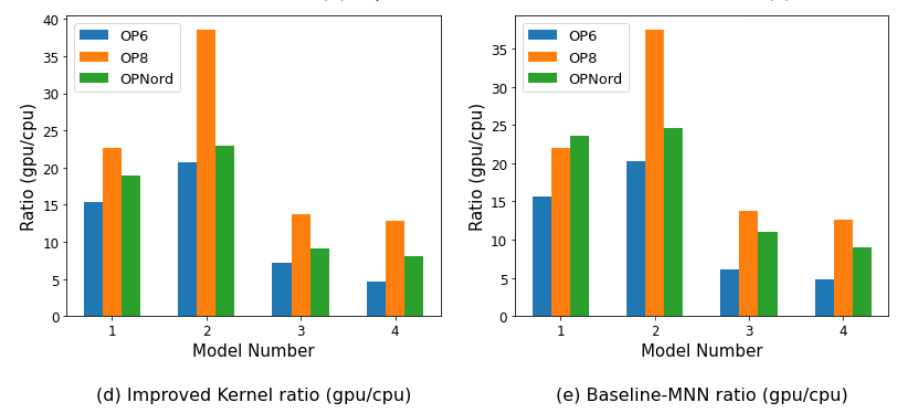

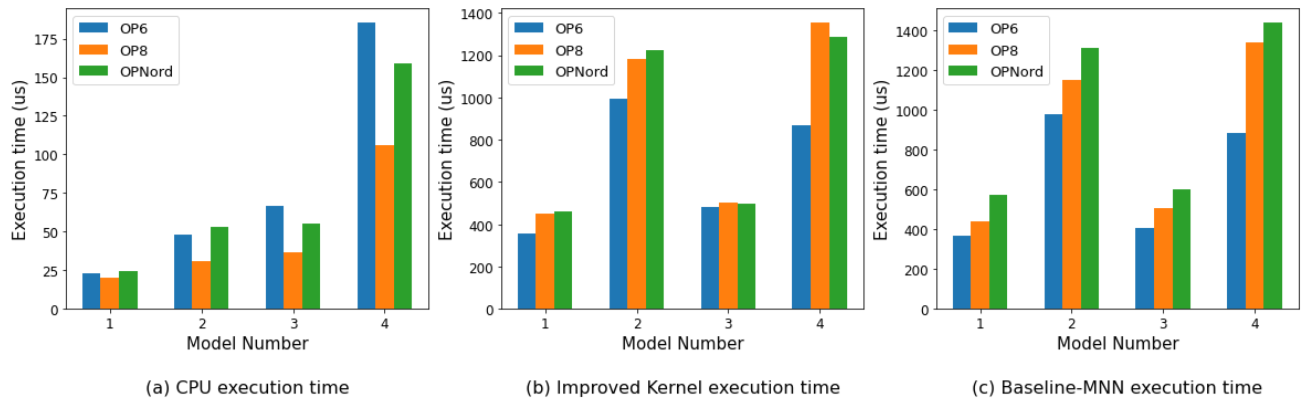

- Hardware: Three devices used in experiments: One Plus Nord, One Plus 6, and One Plus 8 Pro. The One Plus 6 is the oldest phone and was released in May 2018. The other two devices were released in 2020, with the One Plus 8 released as a flagship and the Nord released as a cheaper alternative. Therefore, the Nord has the older version of Adreno GPU but has a newer CPU compared to the One Plus 6.

Profiling Tools: (1) GPU timer and (2) OpenCL profiler. (1) GPU timer is a tool in the OpenCL API that allows an Event object to be attached to a kernel invocation. The Event object is a bookkeeping tool that tracks (a) time it takes to add the kernel call onto the command queue, (b) the time the kernel spends in the queue, and (c) kernel execution time on the GPU. The MNN framework also provides an option to use (2) the OpenCL profiler, which tracks all the operations being performed and reports their time to execute. It uses the GPU timer for execution time and further reports its time to copy data to and from the GPU.

Study Design: After optimizations, the matrix multiplication kernel on the GPU is faster than on the CPU on all the tested smartphones. Next, the kernel was incorporated into the MNN training API to test backpropagation performance. The MNIST dataset is used. The paper reports the backward propagation time on all the devices for each of the models at a fixed batch size of 32. Furthermore, the paper reports the ratio of execution time on the GPU over the execution time on CPU. A simple feed-forward network model with four layers and nodes (784 → 256 → 128 → 16) was used. The optimized kernels did not help improve GPU’s performance over CPU for training.

Alternate Model Architectures: Due to the unexpected results which showed that CPU training outperformed GPU training, the authors repeated experiments with different model architectures to test how network size affects the latency. The authors chose randomized inputs (matrices filled with random numbers). Feedforward networks with the following shapes were used:

- Model 1: 16 → 16 - Model 2: 16 → 16 → 16 → 16 - Model 3: 256 → 256 - Model 4: 784 → 256 → 128 → 16

Results

- The authors find that for backpropagation, the ratios of GPU execution time to CPU execution time using both standard MNN kernels and the authors’ optimized kernels are positive. This indicates that GPU training time is at least an order of magnitude slower than CPU training time. Interestingly, this ratio decreases as network size increases for the four model architectures the authors tested.

- There appears to be an error or at least something unclear in the paper: the authors state “Then, our optimized GPU kernels improve the GFLOPS remarkably from 5, 10, 15 GFLOPS to 25, 40, 70 GFLOPS on One Plus Nord, One Plus 6, and One Plus 8 Pro, respectively” however the following graph appears to contradict or at least not be consistent with this statement. The graphs suggest that the “improved” kernels are an order of magnitude slower than the CPU baseline.

Conclusion

- The authors observe that for the devices tested, training on mobile GPUs is much slower than that on mobile CPUs. The authors attempted GPU kernel optimization to maximize the computation parallelism but experimental results continue to show that overall training time on GPU remains higher than CPU. This indicates that memory bandwidth is a major factor contributing to the inefficient training on mobile GPUs.

Alex’s Comments

I did not provide notes for some major sections of this paper because I was most interested in the question “how feasible is it to train large networks on mobile devices?”. This paper suggests the answer is “not very feasible” considering that the authors’ data shows that in the absolute best case, GPU training is >5X slower than CPU training.

However, I hesitate to fully accept that conclusion. First, the error I detected in the paper gives me pause. Furthermore, the authors only tested networks that are very small by today’s standards. It would have been valuable to train much larger networks and touch the upper limits of GPU memory on the mobile devices tested. Lastly, matrix multiplication is among the most studied problems in computer science. There is a lot of optimization that can be done to accelerate this operation, and I don’t see any citations of the many papers published on the topic. I would have liked to see deeper profiling supporting the claim that memory bandwidth is the bottleneck as well as exploration of optimization techniques to counteract this bottleneck.

The authors could have gone in two alternate directions to make this a great paper: either exhaustively test existing operators on mobile devices with many different network sizes and operator implementations or exhaustively explore optimizations for some combination of device + library + relevant network architecture.